- 5-4-3-2-1

- Posts

- The Finality of Everything by Lawrence Yeo

The Finality of Everything by Lawrence Yeo

Tomorrow is not guaranteed for any of us, yet we live life as if a fresh day awaits us each morning.

Tomorrow is not guaranteed for any of us, yet we live life as if a fresh day awaits us each morning. This is the paradox of our existence: we are aware of our finiteness, but view life through the lens of the infinite. Perhaps this was evolution’s way of patching up our minds to keep an existential crisis at bay. After all, if we truly lived everyday like it was our last, we’d find ourselves in enough precarious situations to prevent the spread of our species.

There are differing opinions about what happens once the finish line is crossed, and I’m certainly in no position to state what does. That’s a mystery that no one has solved, and it’s unclear if anyone ever will.

However, if we break life down to a series of smaller moments, then we can catch a glimpse of what crossing that finish line feels like. Every part of life is finite, and whether we realize it or not, that line will be crossed for everything we do.

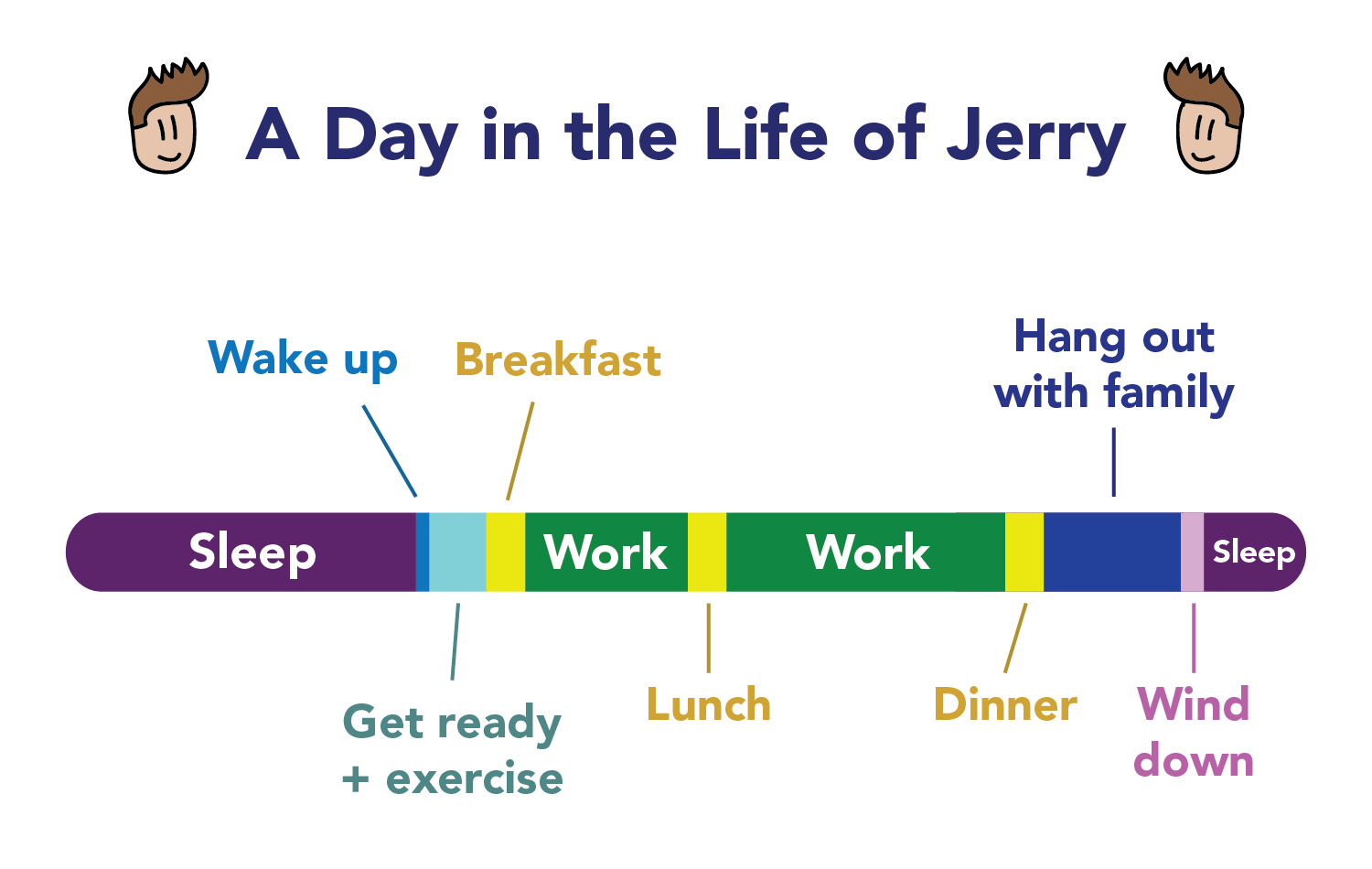

Consider a typical day in the life of a man named Jerry:

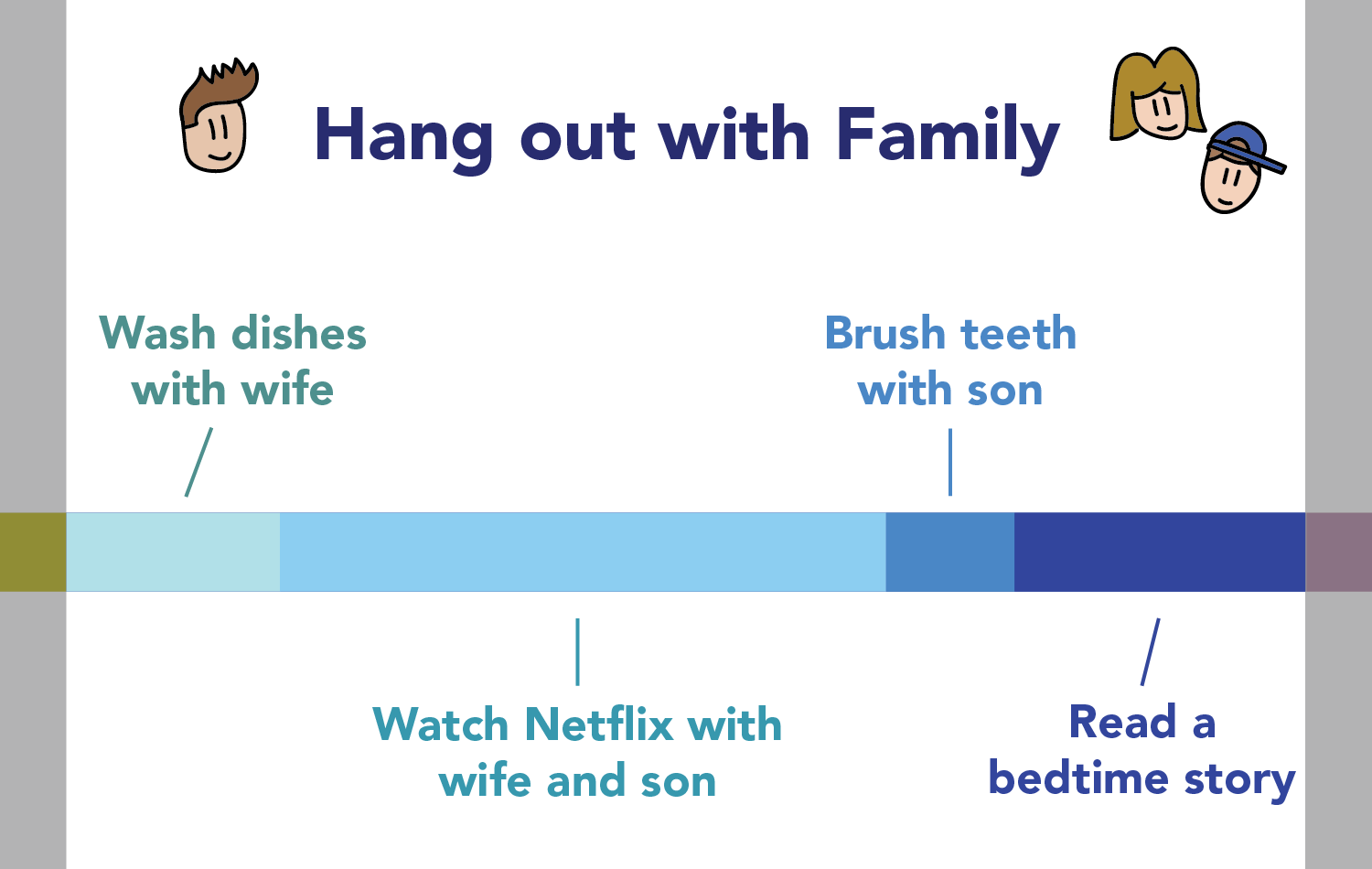

Even though we’ve split up his day into these smaller chunks of time, we can go more granular than that. Let’s zoom into one of these sections, the part where Jerry gets to hang out with his wife and five-year-old son after dinner:

Of these four events, there are some things that will last longer than others. If Jerry stays married, he will probably continue to wash the dinner dishes with his wife for the rest of his life. It’s a routine that both of them have collectively subscribed to, and the only way it would end is if one of them falls ill or passes away. These are the things that end due to the finiteness of life, rather than the finiteness of the moment.

Most things in life, however, don’t end because life itself ends. They end because circumstances change: people grow older, learn more about themselves, shift their view of the world, and adapt accordingly. Jerry’s five-year-old son will one day be ten, and will no longer want to brush his teeth with his dad anymore. There will be a final time when Jerry helps to brush his son’s teeth, and it will happen in a matter of a few years or months, not an entire lifetime.

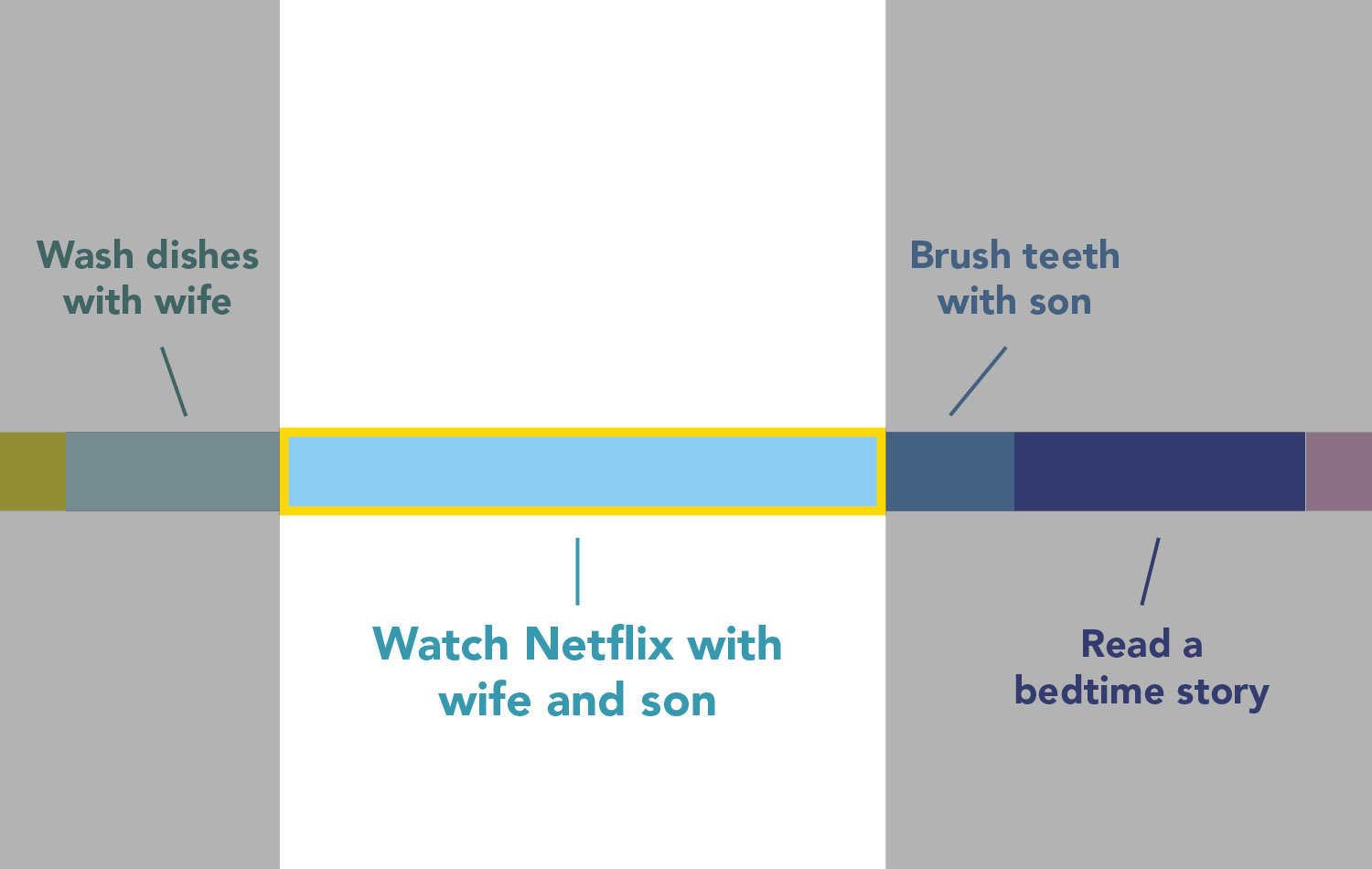

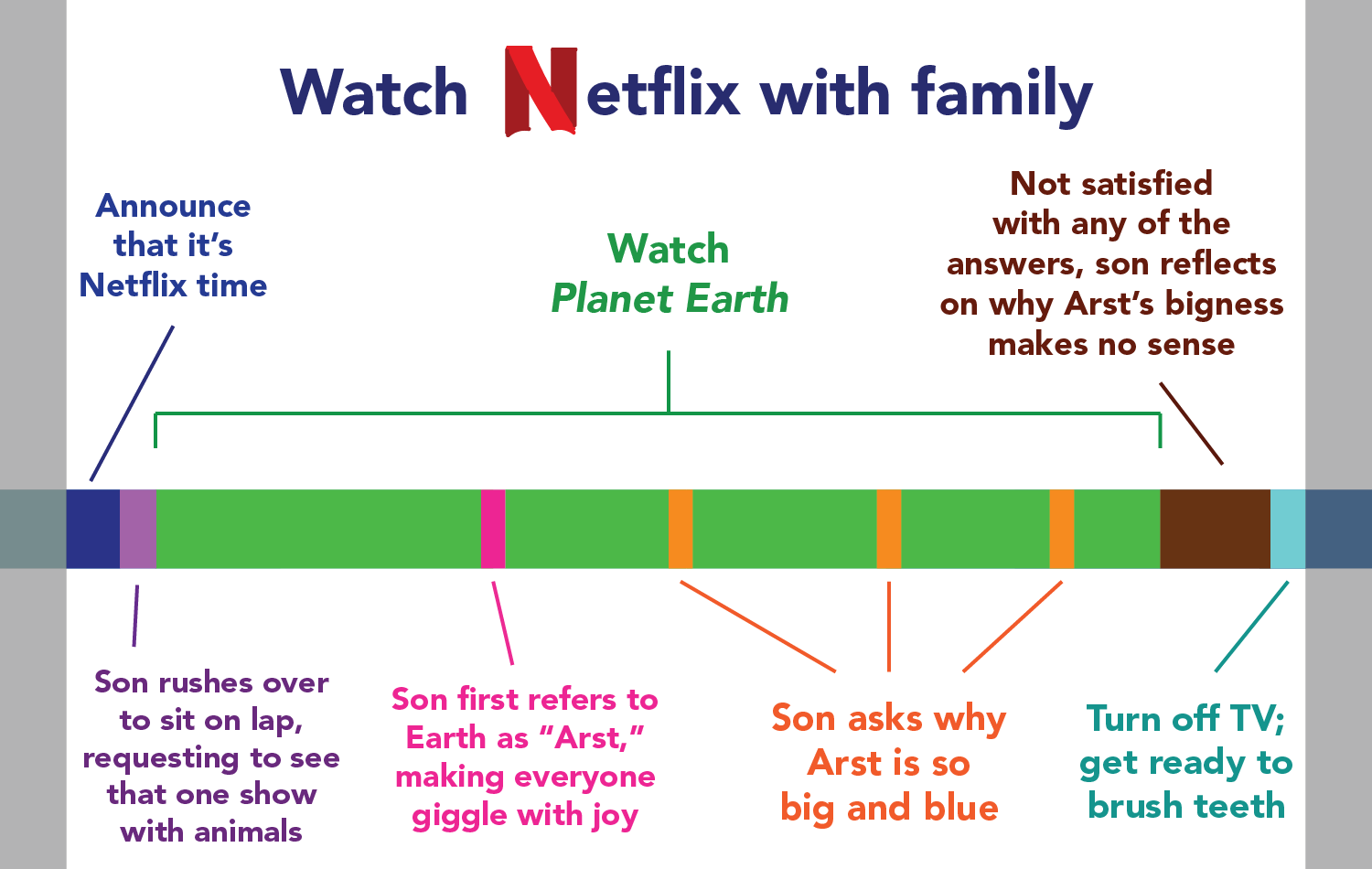

This holds true for every moment, down to all the smaller components that comprise them. Let’s take the “watch Netflix with his wife and son” moment:

And break them down into micro-moments that make up that Netflix-viewing session:

While it’s true that there will be a final time Jerry watches Netflix with his family, what will be more immediate is the final time he experiences the micro-moments that comprise it.

There will be a final time his son rushes to sit on his lap.

There will be a final time his son excitedly requests him to turn on Planet Earth.

There will be a final time his son asks him why the Earth is so big and blue.

There will be a final time his son pronounces Earth as “Arst”.

While Jerry may grow a bit annoyed at how many times his son asks him why Arst is so big and blue, the reality is that each of those moments are precious. This type of earnest and blatant curiosity won’t last forever, let alone a few years. Soon enough, his son will realize that he’s been pronouncing Earth wrong and that Jerry doesn’t have all the answers to everything. The final time for these micro-moments will happen soon, and Jerry won’t even realize when the last time has happened.

This makes me think of all the micro-moments in my life, and the emotions that come with almost all of them. Each of them make me feel a certain way when they occur, but when I’m aware of their finality, I can understand how precious they really are.

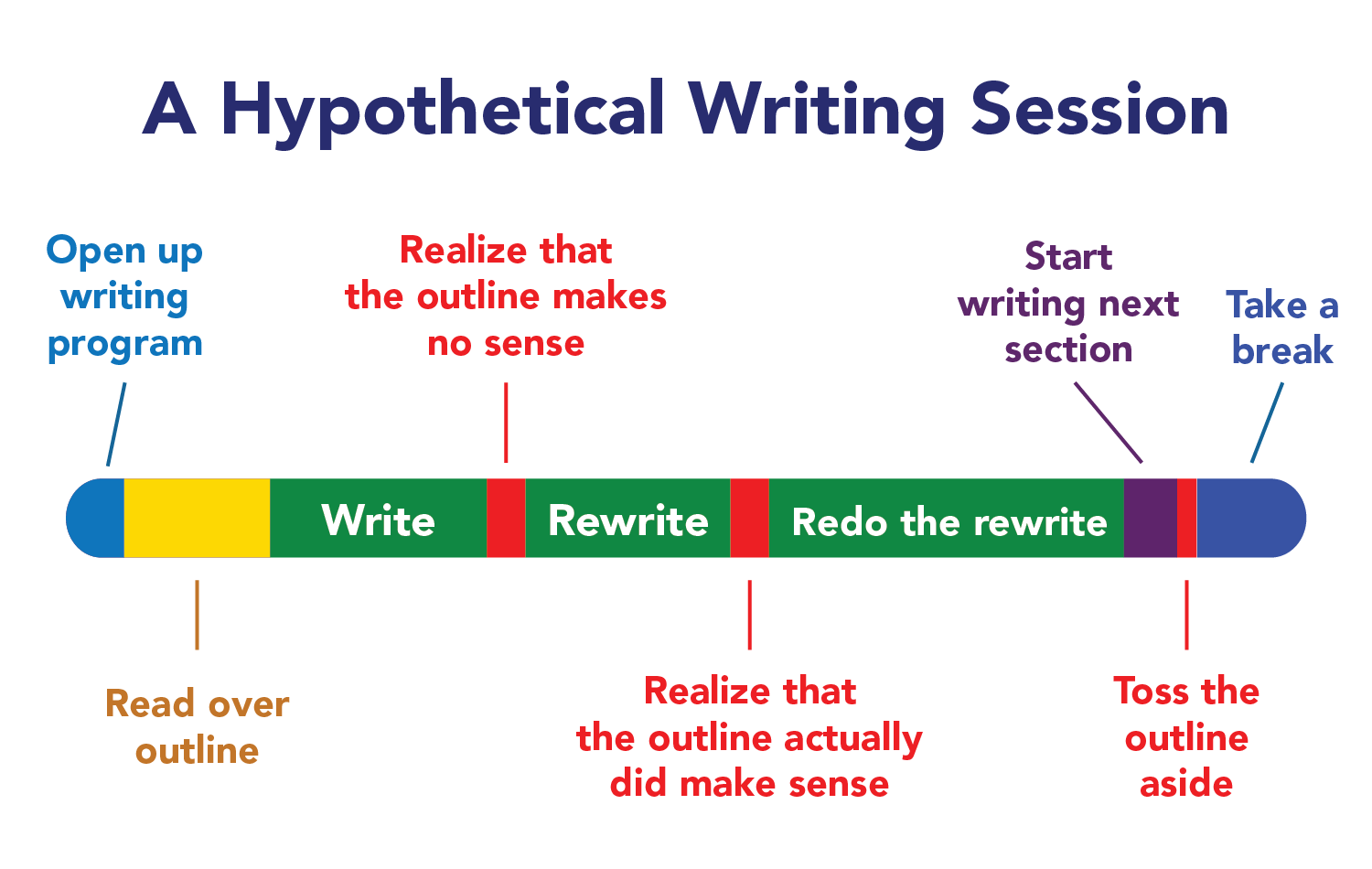

This applies to all aspects of life, including the moments we have with our work. To give a personal example, here are the micro-moments that can make up a potential writing session for a post:

All the micro-moments I’ve marked in red are the ones that can be quite annoying. Trying to make the jagged pieces of a post fit and revising whole sections of written material can get pretty frustrating, but there will be a last time I do these things for this particular post (and for all of writing in general). And when that final time has passed, I will be thankful for it; after all, the challenges of a creative project are what make it such a worthwhile endeavor.

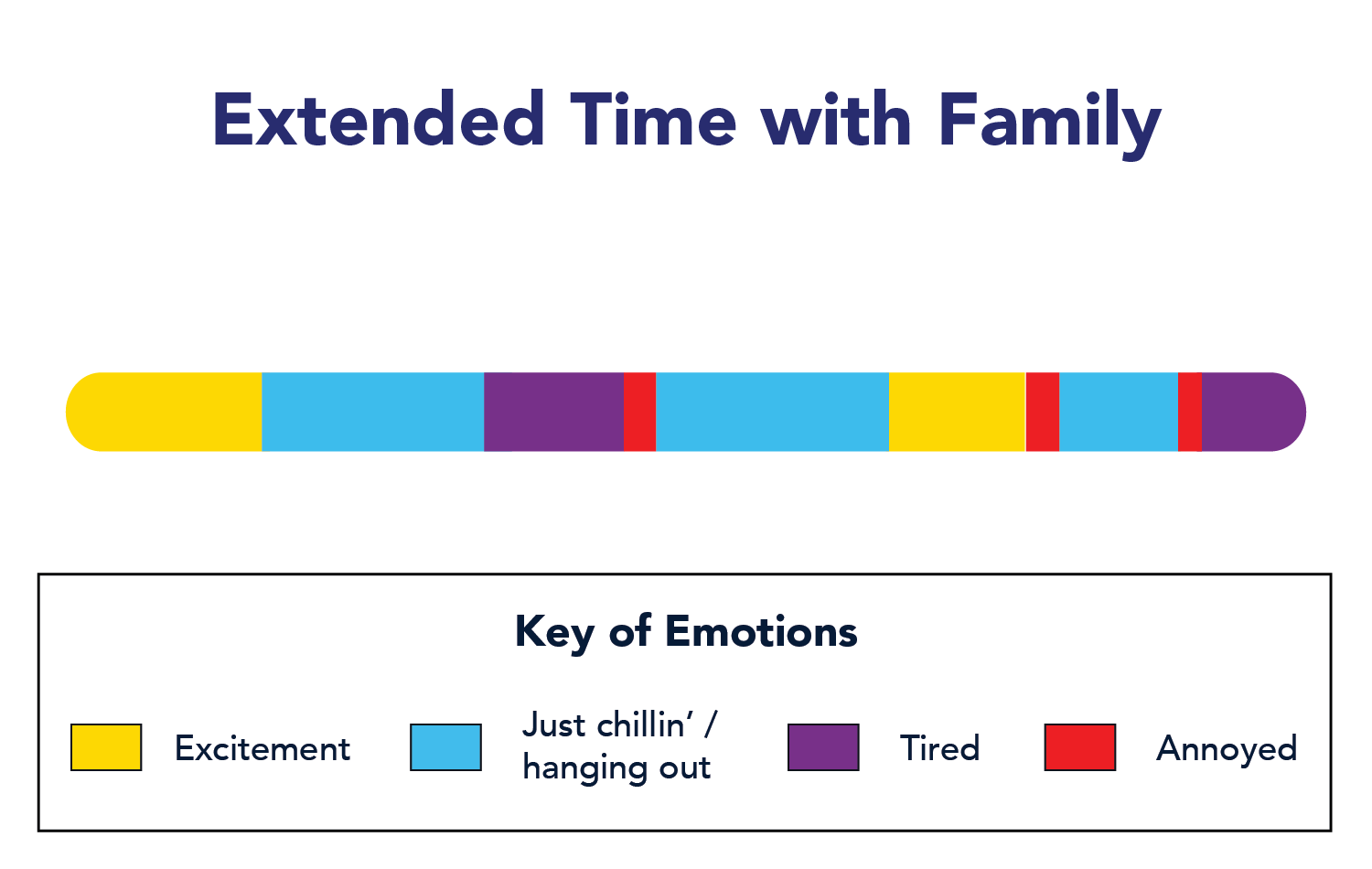

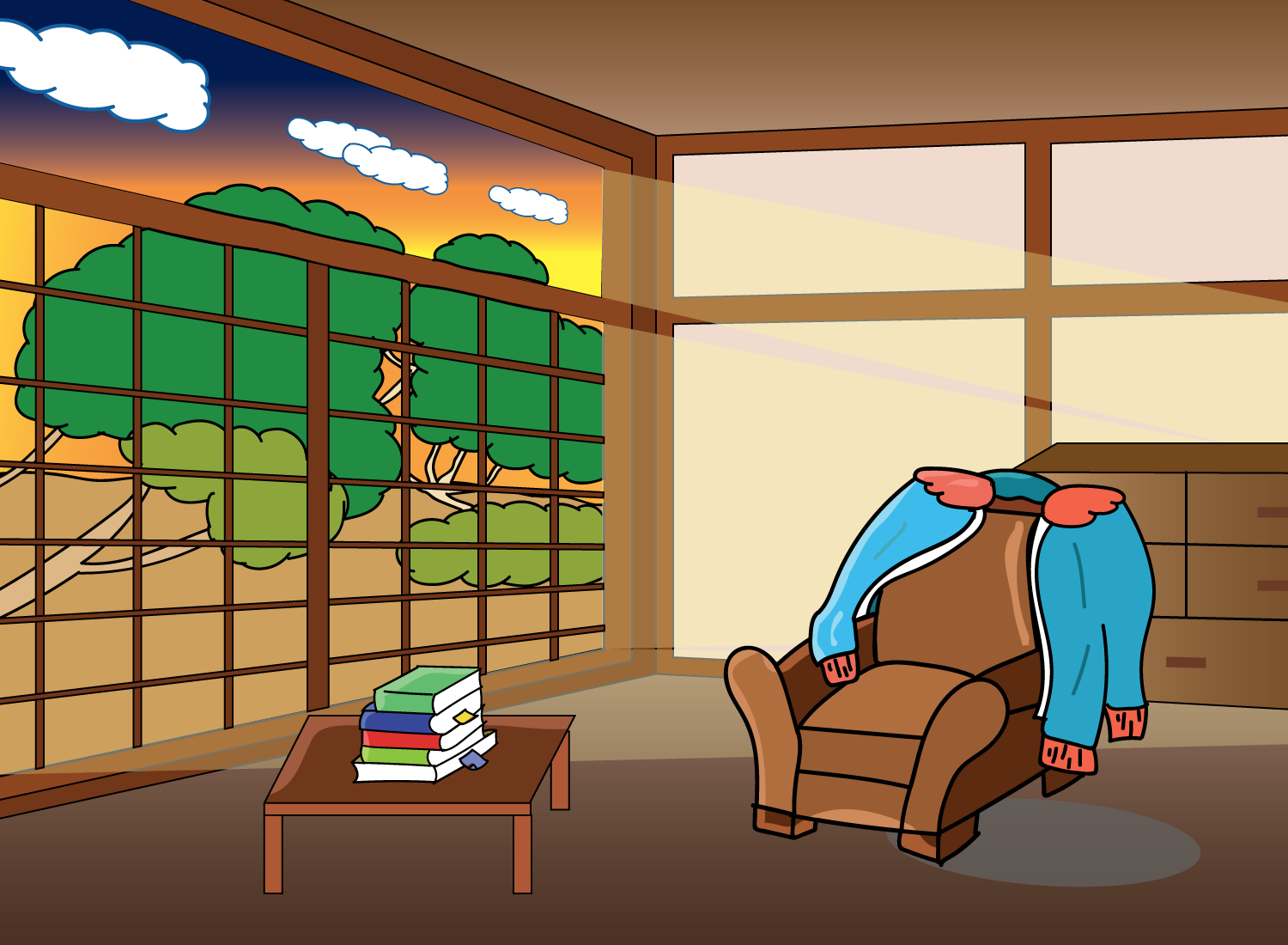

While work is one example of this phenomenon, I think the most poignant of all the micro-moments are the ones we share with family. There are so many unique dynamics that arise from being intimately connected to people that we had no say in choosing, which leads to a range of polarizing emotions (from eternal gratitude to mind-numbing frustration). This is why an extended time with family can look a little something like this:

I’m fortunate enough to have two very loving parents, yet I still have those red micro-moments where the annoyance factor can be high. I have thirty-some-odd years of experience of being someone’s son, but it looks like no matter how high that number gets, I will always be my parents’ little kid. I’m constantly being told how to do things better (I was recently told that everything I knew about doing laundry was wrong), how I need to switch up my diet (I was recently told that I’m drinking too much water), and how to dress in case the weather is chilly.

My parents simply want the best for me, but perhaps it’s hard for them to reconcile their memories of me as a helpless child with the reality of my independent adulthood. This leads to some of those tense moments where they’re trying to impart their habits and views on a mind that is no longer porous to all their suggestions. We all experience this in some manner; it’s just a question as to what degree it is felt.

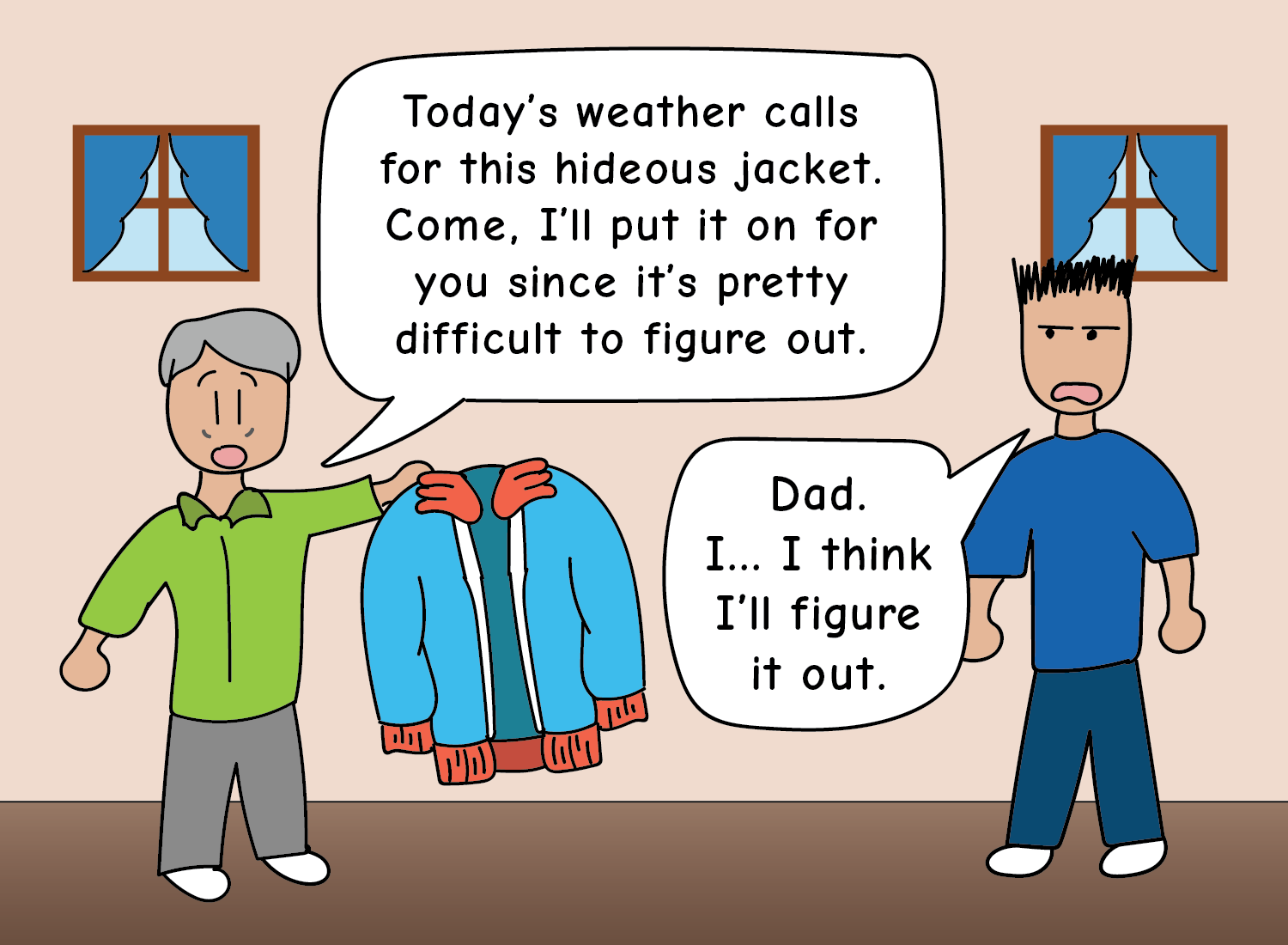

In my case though, it’s important to remember that all of my parents’ intentions come from a place of deep care and love. I may feel a bit annoyed when my dad tells me to put on an unbearably thick jacket in slightly chilly weather, but he’s doing it because he’s truly concerned about my well-being. Not many people in this world give a damn as to whether or not I’m kept warm, and I should be grateful that I have someone that does.

But the easiest way to keep this in perspective is to remember that there will be a final time my dad reminds me to put that jacket on. There will be a day when it’s slightly chilly outside, and I’ll look at that jacket, wishing upon the heavens that he could be there to put it on me one more time. What was once an annoying thing I brushed off will be the one thing I’d give anything for, but nothing I offer will be able to bring that moment back.

Understanding the finality of everything brings a clarity that only a wiser version of myself can see. If I know that one day I’ll long for the very things I routinely gloss over, how can I consciously neglect those moments again? Perhaps the best way to give every moment a fresh start is not to redo it, but to be aware of the finish line that awaits each one.

Reply